Neurodivergent women are super kind

June 16th 2024 is the 7th annual Neurodiversity Pride Day worldwide. Today we are celebrating the first large sample strengths-based study of autism and ADHD in women and AFAB. How refreshing.

Celebrating neurodivergent strengths

As a positive psychology coach, I help neurodivergent humans flourish by working with their strengths. There continues to be a lot of emphasis on ADHD and autistic “deficits” and very little research exploring our strengths.

Additionally, much to my frustration, ADHD and autism medical studies continue to be dominated by male participants. So I humbly asked the women I am co-designing a new self-screening service for ADHD and autism, if they would let me profile their strengths.

Today we are celebrating the first large sample strengths-based study of ADHD and autism in women, non-binary and AFAB. How refreshing!

136 neurodivergent women and AFAB took part in this research, all ADHD, autistic or AuDHD. Women and minority genders face barriers to ADHD and autism diagnosis; we welcomed those who self-identified as well as those medically diagnosed to widen access to participation.

The majority of diagnosed participants were “late-discovered”. The median age of diagnosis was 38 for ADHD and 39 for autism.

Super kind

A remarkable finding was that ADHD and autistic women and AFAB are high in compassionate empathy - trait kindness. We are quick to help others in need. This is remarkable because the autism diagnostic criteria states we have “deficits in social-emotional reciprocity”.

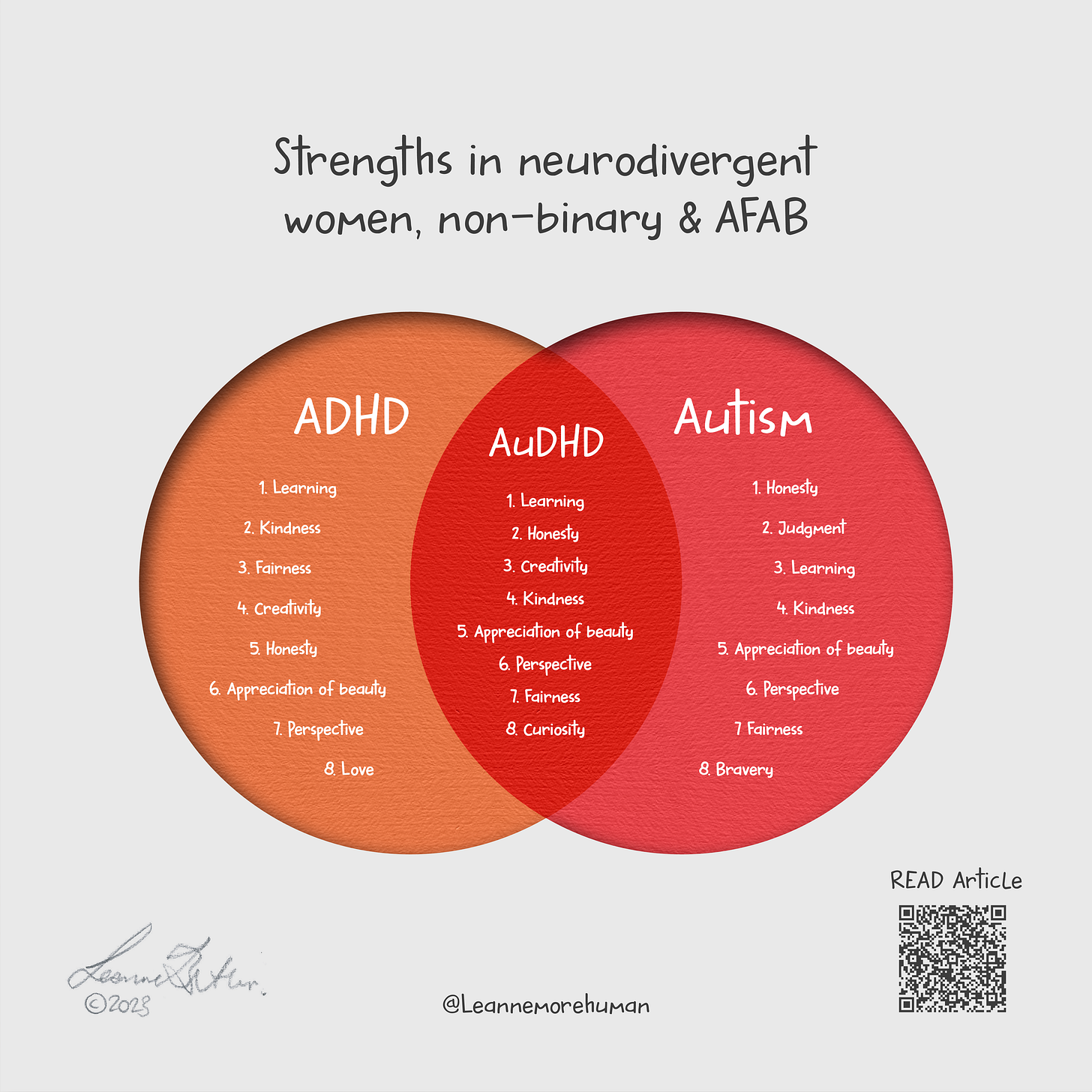

Like neurotypical women, neurodivergent women have high interpersonal strengths. The top 5 strengths for neurodivergent women, non-binary & AFAB were

Love of learning

Honesty

Creativity

Kindness

Appreciation of beauty

Simon Baron-Cohen, a Cambridge professor who studies autism, argued that women could not be autistic because women are hyper empathisers and not hyper-systemisers (Cohen, 2002). He was wrong. Ranking at 6 was perspective - systemising.

A word about sex and gender

Sex and gender are distinct concepts. “Female” and “male” refer to sex assigned at birth. Gender identity refers to a person's deeply felt, internal, and individual experience of gender.

Research shows a high degree of sexual and gender diversity within the autistic and ADHD community. 1 in 10 participants did not identify as a woman and are proudly gender nonconforming.

Genders included in this research were women, trans women, non-binary, genderqueer, gender-fluid, femme-leaning, and agender. For this article, I will respectfully use neurodivergent women and AFAB (assigned female at birth).

What is positive psychology?

Positive psychology is the scientific study of how we can cultivate purpose and wellbeing and reach “optimal human functioning” (or “flourishing”). Positive psychology coaching is a strengths-based approach to change.

Strengths vs deficit-based approach

The 80-20 deficit bias holds that humans waste 80% of our energy focusing on deficits or problems to be fixed. This leaves only 20% of our time and energy for opportunities, solutions, or strengths (Cooperrider & Godwin, 2011, 2012). And this is far from productive.

Positive psychology argues that if we flip this ratio and focus 80% of our effort on our strengths, we create the conditions for optimal human functioning (flourishing).

The medical model describes ADHD and autism as “disorders” that are characterised by deficits. The neurodiversity movement holds that ADHD and autism involve a mixture of unique strengths and challenges. ADHD and autism are not disorders that can be “fixed” or “cured”. We are different, not disordered.

Positive psychology offers an alternative approach to the medical model that is overly concerned with remediating our “deficits”. Positive psychologists believe working with our strengths boosts overall mental health and wellbeing, in turn reducing our difficulties.

Discover your neurodivergent strengths (in under 10 mins)

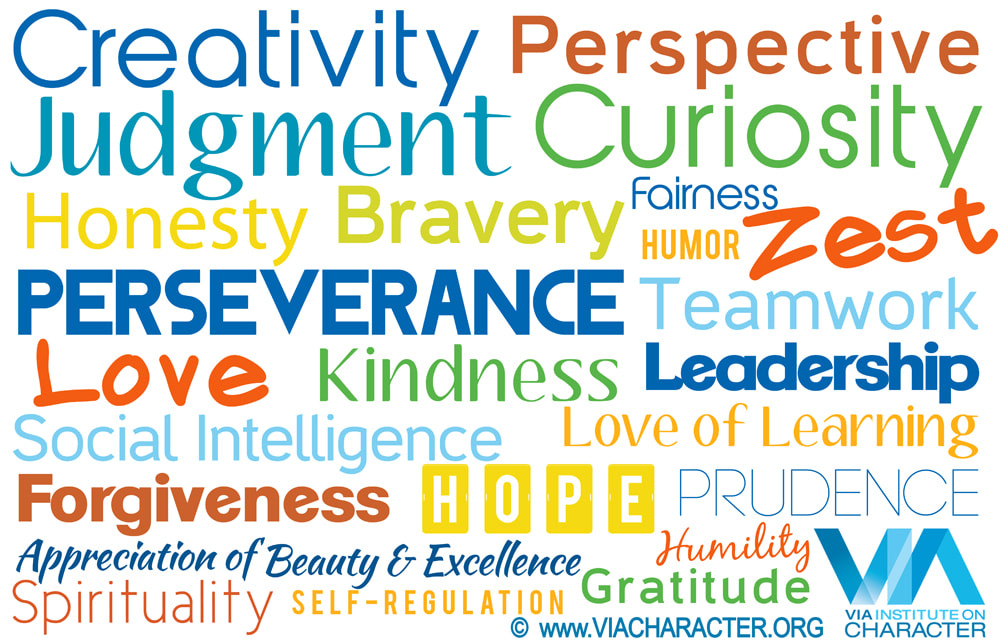

Everyone who participated took the VIA survey, a positive psychology survey that measures character strengths. There are 24 strengths.

Simply taking this survey has been shown to improve wellbeing. Humans who actively use their strengths show reduced stress, anxiety, and depression and increased happiness and wellbeing.

To take the VIA, follow this link.

Celebrating our neurodivergent strengths

The majority of the group (85 humans) were AuDHD. Their strengths illustrate the overlap between ADHD and autism. The top five strengths of this group were Learning, Honesty, Creativity, Kindness, and Appreciation of beauty.

Our findings replicate previous positive psychology studies with smaller samples. A 2022 study with 47 autistic participants (mostly women) found that their top 5 strengths were honesty, appreciation of beauty, learning, fairness, and kindness (Nacoon et al., 2022).

1. Love of Learning

Intelligence differences are a classic sign of autism. An impressive 59% of our research sample reported intellectual giftedness. Of those, 80% identify as autistic (the remainder identify as ADHD).

ADHD and autistic women are often very studious and hard-working. This doesn't fit with the “naughty ADHD schoolboy” stereotype. The ADHD schoolgirl is the teacher's pet. The smartest girl at school is often autistic.

ADHD and autistic women love talking about their favourite subjects. This doesn’t fit with the autism diagnostic criteria that specify “reduced sharing of interests”. The opposite behaviour is observable in women.

The term autistic “info dumping” is trending on social media. This has negative connotations with “trauma dumping” and is, in my opinion, more shame-inducing than “monologuing”. This continues to overlook a key strength.

ADHD and autistic women are generous with their knowledge and love learning. This is a strength, not a deficit.

As an autistic woman, I have to know EVERYTHING about a topic. Over the past two years, I’ve read every single paper I could find about ADHD and autism in women. ALL of them. I’m hyperlexic.

I have always had a passion for coaching and mentoring others. This year, I decided to use that strength to start publishing everything I’ve learned on my journey of self-discovery. I look forward to facilitating group training and learning experiences and empowering neurodivergent women with knowledge.

2. Honesty

Honesty was the #2 strength among those who identified as AuDHD and #1 among those solely autistic. Among those with ADHD and not autism, honesty ranked at #6. Autistics are known for their honesty and direct communication style. Honesty and intolerance for lying are autistic traits.

AuDHD and autistic women demonstrated significantly elevated honesty relative to neurotypical women, for whom honesty ranked #7 (Linley et al., 2007).

In individual differences, the trait honesty-humility positively correlates with prosocial behaviour (kindness) and negatively correlates with narcissistic and antisocial personality disorder (Wertag et al., 2018). Both conditions affect three times as many men (Alegria, 2013; Weidmann et al., 2023).

Our honesty makes us vulnerable to victimisation and manipulation by dark personalities. Naive neurodivergent girls expect others to mirror their honesty, assuming good intentions. “Pinocchio syndrome” describes a boy with narcissistic and antisocial traits (Novellino, 2000).

Autistic women eventually grow wise to manipulation, deceit and “gaslighting”. AuDHD women with victim sensitivity are more inclined to suspect others of untrustworthiness and second-guess their intentions (Gollwitzer et al., 2015).

I strategically decided to start a business working with neurodivergent women and AFAB because I know that, statistically, I can trust women more than men.

Theatrical release poster - Pinocchio 1940.

3. Creativity

Creativity ranked significantly lower in the solely autistic group, suggesting that hypercreativity has something to do with our ADHD biology.

The broaden-and-build theory in positive psychology posits that positive emotions energise us, increasing lateral thinking and our ability to generate ideas. Negative emotions deplete us of energy and reduce our ability to see options (Fredrickson, 2001).

Character strengths are dynamic and fluctuate with context. If you have depression, your creativity and strengths related to positive emotions, like humour or love, will drop. Depression is the enemy of creativity. A loss of hope and the inability to see options can leave us feeling stuck.

Neurodivergent women can increase their creativity by engaging with their special interests and passions and by focusing on their strengths.

ADHDers are high in humour. (It’s among the top 10 strengths.) Laughter is contagious and brings humans together. Writing down three funny things that happened each day has been shown to improve wellbeing and boost creativity (Gandar et al., 2013).

Research shows ADHD difficulties increase with stress, burnout, depression and PTSD, all of which increase cortisol and reduce dopamine and serotonin. Laughter boosts positive emotions and buffers against stress, releasing dopamine and serotonin. Laughter might be the only side-effect-free ADHD medication.

This is your reminder to laugh next time you send an impulsive email or drop your phone down the toilet.

4. Kindness

Compassionate empathy or empathic concern refers to the motivation to help another person in need. In simple human terms, it is kindness. Kindness ranked at #2 for ADHDers. Neurodivergent women are super kind.

In psychological research, this is referred to as prosocial behaviour. Prosocial behaviour refers to “voluntary actions intended to help or benefit another individual or group of individuals” (Eisenberg & Mussen, 1989, p3). Examples include cooperating, helping, sharing, volunteering, and donating (Arthur et al., 1986).

Neurotypical women are higher in prosocial behaviour than men (Olmos, 2023). ADHD women show equivalent levels of kindness to neurotypical women - kindness ranking #2 (Linley et al., 2007). Other research has shown autistic women reciprocate at levels equivalent to their neurotypical peers (Wood‐Downie et al., 2020).

According to the research, neurodivergent women are “people pleasers” and have high social motivation. We are always saying sorry.

This doesn’t fit with the autism diagnostic criteria which looks for “deficits in social-emotional reciprocity” specifying “absence of interest in peers” and “difficulties in making friends” as key indicators. We are friendly.

Overusing a strength like kindness can be detrimental to wellbeing (Niemic, 2019). You can moderate overuse by practising self-care before caregiving.

Other kindness interventions include engaging in random acts of kindness or paying forward a good deed without expectation of reciprocity (Bukley, 2014; Kraft & Cross, 2015).

Kindness is my #3 strength. I’m operationalising my kindness into a pay-it-forward business model. This year, for every four humans who coach with More Human through Access to Work or self-funded, we will offer free brief unemployment coaching to one neurodivergent human who is ineligible for support.

Write to leanne@wearemorehuman.co.uk if you need an ear.

Photo from The Female Lead

5. Appreciation of Beauty

Neurodivergent women have sensory differences that enhance their sensitivity to the world around them. While sensory processing differences are formally part of the diagnostic criteria for autism, sensory processing differences are increasingly being recognised as affecting ADHDers too.

Appreciation of beauty was elevated in both the autism and AuDHD group, ADHDers ranked at 6. Noticing details that others do not is an autistic trait.

The research shows that autistic women experience higher levels of sensory distress compared to men (Cardon et al., 2023; Osoro et al., 2021). This is a key sex difference in autism and, by inference, ADHD. Hypersensory sensitivity means we experience the world around us with greater intensity; this can lead to irritability and emotional meltdowns.

A positive aspect of sensory processing differences is that we are very good at noticing the beauty around us. Walking in beauty and nature will improve your wellbeing (Diessener et al., 2015). Engaging with sensory soothers can reduce sensory distress.

I’m a huge fan of mindfulness. Mindfulness involves bringing your attention to the current moment and actively engaging with the world using your senses. It’s been shown to improve ADHD symptoms, autistic difficulties, anxiety and depression (Agiues et al., 2024; Hofmann & Gómez, 2017; Poisant et al., 2019).

If you want to get started with mindfulness, read this book or book me for coaching.

Focusing less on our challenges

Positive psychology advises against focusing on our difficulties and encourages us to focus on our strengths. The top 5 challenges for this group (from the bottom and in reverse order) were self-regulation, perseverance, zest (energy) and prudence.

1. Self-regulation

The VIA defines self-regulation as “regulating what one feels and does; being disciplined; controlling one’s appetites and emotions.”

ADHD and autistic women experience intense emotions and emotional overwhelm. This is in part due to our hormones.

ADHD impulsivity and inattention symptoms, autistic repetitive behaviours and sensory distress increase with PMS and depression. Depression is elevated during the luteal phase of our menstrual cycle, when progesterone levels rise, and post-childbirth and menopause, when estrogen levels drop.

This link may, in part, explain why autistic and ADHD women are more likely to be diagnosed during hormonal transitions, such as after the birth of a child or in perimenopause. (At the same time, women reported that GPs are brushing off undiagnosed ADHD or autism to hormones.)

Research shows high levels of premenstrual exasperation and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) in women with ADHD and autism. However, the samples have been small, and the results are inconsistent (Groenman et al., 2022; Lever and Geurts, 2016; Obaydi and Puri, 2008).

Self-reporting of PMDD may be inaccurate due to poor awareness about the disorder amongst neurodivergent women and the absence of prescreening. Charity IAPMD offers a FREE PMDD self-screening.

2. Perseverance

Perseverance is defined in the VIA as “finishing what one starts; persisting in a course of action despite the obstacles; taking pleasure in completing tasks’ and - wait for it - ‘getting it out the door”.

ADHD and autism cause executive functioning difficulties that make it difficult to sustain attention and focus. Enthusiastic starters, not always finishers. Unless it’s the end of somebody else’s sentence.

ADHDers tend to avoid tasks they don’t find interesting and prioritise what they enjoy. On the upside, ADHDers are more likely to abandon goals not worth persisting with and pursue goals that align with their values, which keeps them psychologically flexible.

3. Zest (energy)

The VIA defines zest as “approaching life with excitement and energy; not doing things halfway or half-heartedly; living life as an adventure; feeling alive as an adventure; feeling alive and activated.”

Some might misinterpret low levels of zest as supporting the widely held belief that ADHD women are more likely to have inattentive type ADHD. But in our research sample of 176 women, 65% of diagnosed women had combined type ADHD, 26% were inattentive, and 9% were hyperactive or unsure. This wasn’t supported.

Low energy levels are better explained by high rates of co-occurring fibromyalgia or long COVID amongst autistic and ADHD women. Fibromyalgia is associated with rheumatoid autoimmune disorders and hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (HeDS) (Haliloglu et al., 2014; Fairweather et al., 2023).

Both hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (HeDS) and fibromyalgia affect women disproportionately at 9:1 (Bartels et al., 2009; Rogers et al., 2017; Tinkle et al., 2017). Autistic and ADHD women are affected by fibromyalgia and HeDS at still higher rates.

Psychiatrist Dr Jessica Eccles (aka Bendy Brain) is researching the connection. She and her team found that 50% of participants with a diagnosis of Autism, ADHD or Tourette syndrome had hypermobility, compared with just 20% of neurotypicals (Csecs et al., 2022). We are far more bendy.

Her latest research showed that neurodivergent humans with hypermobility syndrome were 30% more likely to be impacted by long COVID (Eccles et al., 2024). The SEDS connective is a charity that offers education and support for neurodivergent humans affected by hypermobility.

Again, character strengths are dynamic and fluctuate depending on context. Many neurodivergent women who participated in this research told us a mental health crisis triggered their late diagnosis over the pandemic. Chronic stress throughout the pandemic has caused increased fibromyalgia, related depression and burnout.

Autistic and ADHD burnout is characterised by chronic exhaustion, increased ADHD symptoms or autistic traits, increased sensory distress, social and emotional overwhelm and temporary loss of skills. 98% meet the clinical cut-off for major depression (Arnold et al., 2023).

Burnout and depression are exhausting.

4. Teamwork

This research found that neurodivergent women have high interpersonal strengths including honesty, kindness and fairness, but have challenges with teamwork. Maybe we do our best work alone, in pairs, or through smaller group interactions?

Autistic and ADHD women are known to suffer from high levels of social anxiety and feel uncomfortable in a group. They may avoid group activities or team sports and enjoy autonomy. Others may gravitate towards the side of the room, to leadership or facilitation roles, preferring not to be a group member.

This is not necessarily a weakness - neurodivergent women are fiercely independent and have a pervasive need for autonomy. We are excellent leaders, and we are likelier to start a business or become solopreneurs.

5. Prudence

The definition of prudence in the VIA is “being careful about one’s choices; not taking undue risks; and not saying things that might later be regretted.” Prudence was significantly elevated in autistics who didn’t identify as having ADHD, ranking at 14, suggesting low prudence is a symptom of ADHD.

ADHDers with combined or hyperactivity are impulsive and engage in risk-taking behaviours. Most of us have had to deal with the shame hangover when we’ve emotionally reacted or blurted out our feelings.

The upside is that ADHDers are likely to take risks and deliver breakthrough products, services, ideas, and innovations. We are “disruptors”, not “disruptive”.

To end

On this neurodiversity pride day, please remember to focus on your neurodivergent strengths, switch off from your difficulties, and have a happy Sunday.

Thank you to everyone who took part in this research.

Thank you especially to A., who volunteered to edit this essay after I prematurely sent my debut article full of typos and without references.

Love my ADHD brain. 🤣

Neurodivergent women are super kind.

Boring details

Who took part in this research?

Thank you to everyone who took part in this research. 176 women were invited to take part. Of the 136 who responded, 39 were medically diagnosed solely with ADHD, 27 were diagnosed with autism, and 20 with AuDHD (both autism and ADHD). The remainder self-identified.

Why was this research done?

This research was done to support the development of a new ADHD and autism pre-diagnostic screening and self-identification service for women and AFAB. This research was conducted with academic rigor and in line with ethical guidelines.

The gender gap in research

This was not a formal medical or psychological study. This was a research pilot.

While research has increased into the lived experiences of girls and women with autism/ADHD in the last five years, there has been little attention on how either condition presents across genders. There is a gender gap in research.

I plan to do a large-scale study of strengths in ADHD and autism across all genders (this time including men) when I return to finish my MAPPCP in September and publish an academic paper on neurodivergent strengths.

I hold a PGDip in Applied Positive Psychology and Coaching Psychology and am working towards the highest level of coaching accreditation with the EMCC.

Limitations of this research

Participants were asked to complete a self-report questionnaire that has not been validated with autistic or ADHD humans. The group fed back that the demographic form at the end uses pathologising language and, critically, omits ADHD!

The research sample consisted largely of highly educated white women. Autistics with an intellectual disability (2.4% of the sample) are all too often excluded from autism research, and our sample does not fully represent them. We recruited on LinkedIn, a professional networking site.

The sample was biased toward women and AFAB who identified as AuDHD or autistic. Soley autistic and ADHDers without autism were relatively underrepresented. However, the number of respondents to the ADHD segment exceeded 30, considered a large sample.

Only 19 participants identified as solely autistic. This equates to around 18% of those who identified as autistic. This is likely due to the high comorbidity rate of ADHD in autism. The research reports that 50-70% of autistics have co-occurring ADHD (Houre et al, 2022).

The sample consisted solely of women and AFAB. 1 in 10 identified as non-binary. I suspect trans were underrepresented. Research shows high rates of LGBQT+ within the autistic community. A large study found that 24% of the trans community is autistic (Warrier et al., 2020.) Future research would benefit from including both sexes, all genders, and a neurotypical control group.

References

Agius, H., Luoto, A. K., Backman, A., Eriksdotter, C., Jayaram-Lindström, N., Bölte, S., & Hirvikoski, T. (2024). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for autistic adults: A feasibility study in an outpatient context. Autism : the international journal of research and practice, 28(2), 403–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613231172809

Alegria, A. A., Blanco, C., Petry, N. M., Skodol, A. E., Liu, S. M., Grant, B., & Hasin, D. (2013). Sex differences in antisocial personality disorder: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Personality disorders, 4(3), 214–222. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031681

Arnold, S. R., Higgins, J. M., Weise, J., Desai, A., Pellicano, E., & Trollor, J. N. (2023). Towards the measurement of autistic burnout. Autism, 27(7), 1933-1948. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221147401

Bartels, E. M., Dreyer, L., Jacobsen, S., Jespersen, A., Bliddal, H., & Danneskiold-Samsøe, B. (2009). Fibromyalgi, diagnostik og praevalens. Kan kønsforskellen forklares? [Fibromyalgia, diagnosis and prevalence. Are gender differences explainable?]. Ugeskrift for laeger, 171(49), 3588–3592.

Baron-Cohen S. (2002). The extreme male brain theory of autism. Trends in cognitive sciences, 6(6), 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1364-6613(02)01904-6

Brehm J. W. & Brehm S. S. (1981). Psychological reactance – a theory of freedom and control. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

Cardon, G., McQuarrie, M., Calton, S., & Gabrielsen, T. P. (2023). Similar overall expression, but different profiles, of autistic traits, sensory processing, and mental health between young adult males and females. Research in autism spectrum disorders, 109, 102263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2023.102263

Contreras, I. M., Kosiak, K., Hardin, K. M., & Novaco, R. W. (2021). Anger rumination in the context of high anger and forgiveness. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, Article 110531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110531

Csecs, J. L. L., Iodice, V., Rae, C. L., Brooke, A., Simmons, R., Quadt, L., Savage, G. K., Dowell, N. G., Prowse, F., Themelis, K., Mathias, C. J., Critchley, H. D., & Eccles, J. A. (2022). Joint Hypermobility Links Neurodivergence to Dysautonomia and Pain. Frontiers in psychiatry, 12, 786916. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.786916

Dew, R. E., Kollins, S. H., & Koenig, H. G. (2022). ADHD, Religiosity, and Psychiatric Comorbidity in Adolescence and Adulthood. Journal of attention disorders, 26(2), 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054720972803

Eccles, J., Cadar, D., Quadt, L., Hakim, A., Gall, N., Covid Symptom Survey Biobank Consortium, ., Bowyer, V., Cheetham, N., Steves, C. J., Critchley, H., & Davies, K. (2024). Is joint hypermobility linked to self-reported non-recovery from COVID-19? Case–control evidence from the British COVID Symptom Study Biobank (Version 1). University of Sussex. https://hdl.handle.net/10779/uos.25461169.v1

Fairweather, D., Bruno, K. A., Darakjian, A. A., Bruce, B. K., Gehin, J. M., Kotha, A., Jain, A., Peng, Z., Hodge, D. O., Rozen, T. D., Munipalli, B., Rivera, F. A., Malavet, P. A., & Knight, D. R. T. (2023). High overlap in patients diagnosed with hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or hypermobile spectrum disorders with fibromyalgia and 40 self-reported symptoms and comorbidities. Frontiers in medicine, 10, 1096180. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1096180

Fredrickson B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. The American psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.218

Gollwitzer, M., Süssenbach, P., & Hannuschke, M. (2015). Victimization experiences and the stabilization of victim sensitivity. Frontiers in psychology, 6, 439. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00439

Groenman, A. P., Torenvliet, C., Radhoe, T. A., Agelink van Rentergem, J. A., & Geurts, H. M. (2022). Menstruation and menopause in autistic adults: Periods of importance?. Autism : the international journal of research and practice, 26(6), 1563–1572. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211059721

Haliloglu, S., Carlioglu, A., Akdeniz, D., Karaaslan, Y., & Kosar, A. (2014). Fibromyalgia in patients with other rheumatic diseases: prevalence and relationship with disease activity. Rheumatology international, 34(9), 1275–1280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-014-2972-8

Hofmann, S., Gómez, A. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions for anxiety and depression. Psychiatric Clinics of North America [Internet]. [cited 3 December 2021];40(4):739–749. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5679245/

Hours, C., Recasens, C., & Baleyte, J. M. (2022). ASD and ADHD Comorbidity: What Are We Talking About?. Frontiers in psychiatry, 13, 837424. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.837424

Lever, A. G., & Geurts, H. M. (2016). Psychiatric Co-occurring Symptoms and Disorders in Young, Middle-Aged, and Older Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 46(6), 1916–1930. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2722-8

Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., Harrington, S., Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2007). Character strengths in the United Kingdom: The VIA Inventory of Strengths. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(2), 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.12.004

Mitolo, M., D'Adda, F., Evangelisti, S., Pellegrini, L., Gramegna, L. L., Bianchini, C., Talozzi, L., Manners, D. N., Testa, C., Berardi, D., Lodi, R., Menchetti, M., & Tonon, C. (2024). Emotion dysregulation, impulsivity and anger rumination in borderline personality disorder: the role of amygdala and insula. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience, 274(1), 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-023-01597-8

Nocon, Alicja & Roestorf, Amanda & Menéndez, Luz. (2022). Positive psychology in neurodiversity: An investigation of character strengths in autistic adults in the United Kingdom in a community setting. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 99. 102071. 10.1016/j.rasd.2022.102071.

Novellino, M. (2000). The Pinocchio Syndrome. Transactional Analysis Journal, 30(4), 292-298. https://doi.org/10.1177/036215370003000406

Niemiec, R. M. (2019). Finding the golden mean: The overuse, underuse, and optimal use of character strengths. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 32(3-4), 453–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1617674

Obaydi, H., & Puri, B. K. (2008). Prevalence of premenstrual syndrome in autism: a prospective observer-rated study. The Journal of international medical research, 36(2), 268–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/147323000803600208

Olmos-Gómez, M. D. C., Ruiz-Garzón, F., Azancot-Chocron, D., & López-Cordero, R. (2023). Prosocial behaviour axioms and values: Influence of gender and volunteering. Psicologia, reflexao e critica : revista semestral do Departamento de Psicologia da UFRGS, 36(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-023-00258-y

Osório, J. M. A., Rodríguez-Herreros, B., Richetin, S., Junod, V., Romascano, D., Pittet, V., Chabane, N., Jequier Gygax, M., & Maillard, A. M. (2021). Sex differences in sensory processing in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 14(11), 2412–2423. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2580

Poissant, H., Mendrek, A., Talbot, N., Khoury, B., & Nolan, J. (2019). Behavioral and Cognitive Impacts of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Adults with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review. Behavioural neurology, 2019, 5682050. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5682050

Rodgers, K., Gui, J., Dinulos, M. et al. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome hypermobility type is associated with rheumatic diseases. Sci Rep 7, 39636 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep39636

Taylor, E. C., Livingston, L. A., Clutterbuck, R. A., Callan, M. J., & Shah, P. (2023). Psychological strengths and well-being: Strengths use predicts quality of life, well-being and mental health in autism. Autism, 27(6), 1826-1839. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221146440

Tinkle, B., Castori, M., Berglund, B., Cohen, H., Grahame, R., Kazkaz, H., & Levy, H. (2017). Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (a.k.a. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome Type III and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome hypermobility type): Clinical description and natural history. American journal of medical genetics. Part C, Seminars in medical genetics, 175(1), 48–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31538

Wertag, A & Bratko, D. (2018). In Search of the Prosocial Personality: Personality Traits as Predictors of Prosociality and Prosocial Behavior. Journal of Individual Differences. 40. 1-8. 10.1027/1614-0001/a000276.

Weidmann, R., Chopik, W. J., Ackerman, R. A., Allroggen, M., Bianchi, E. C., Brecheen, C., Campbell, W. K., Gerlach, T. M., Geukes, K., Grijalva, E., Grossmann, I., Hopwood, C. J., Hutteman, R., Konrath, S., Küfner, A. C. P., Leckelt, M., Miller, J. D., Penke, L., Pincus, A. L., . . . Back, M. D. (2023). Age and gender differences in narcissism: A comprehensive study across eight measures and over 250,000 participants. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 124(6), 1277–1298. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000463

Wood-Downie, H., Wong, B., Kovshoff, H., Mandy, W., Hull, L., & Hadwin, J. A. (2021). Sex/Gender Differences in Camouflaging in Children and Adolescents with Autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 51(4), 1353–1364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04615-z